Your guide to cooking substitutions when you’re missing an ingredient : Life Kit : NPR

Photo Illustration by Becky Harlan/NPR

Photo Illustration by Becky Harlan/NPR

Have you ever been in the middle of cooking dinner when you suddenly realize that you don’t actually have all the ingredients the recipe calls for?

This happens to me all the time. Sometimes, I don’t even try to get all the ingredients in a recipe, because my spice shelf is jam-packed, my counter doesn’t need another type of vinegar and I definitely have to use up that box of cremini mushrooms before they go bad. Instead, I swap out ingredients based on what I’ve got on hand, or if I’m cooking for someone with dietary restrictions or allergies.

It’s taken years to get comfortable improvising in the kitchen, and I still do plenty of Googling to get ideas of what I can swap out. But learning what makes up flavor, knowing my palate and getting comfortable with taking risks have been key to unlocking how to substitute while cooking – and it’s made cooking a lot more fun.

Here are some tips to help you get there, too.

Get to know your tastebuds

Lean into your senses to understand what you’re tasting and how you’re tasting it.

“I think one important way or one useful way to think about it is to understand that our perception of taste is something that comes both from what we perceive on our tongue … combined with what we smell,” explains Kenji López-Alt, a professional chef and food writer based in Seattle.

To get started, ask yourself some questions: Where does the flavor hit your tongue? Do you feel the heat from something spicy? What do you smell? Does the smell impact what you taste? Does the bite you just took feel creamy or silky in your mouth? Is there a little sweetness coating your tongue? Are your cheeks contracting like you just sucked on a lemon? Does the dish taste bland or is it popping with the flavor of the tomatoes you added?

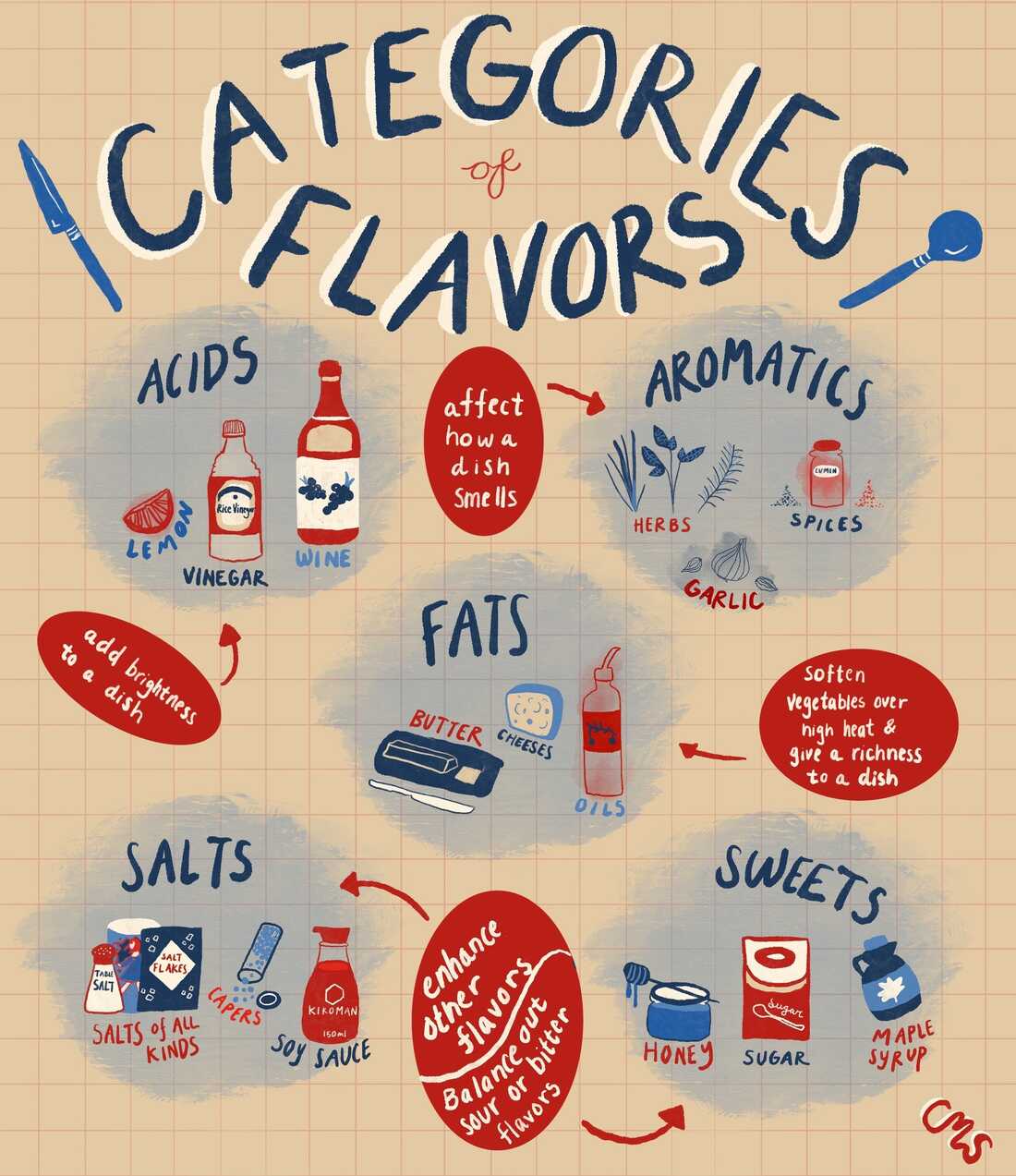

As you start to understand those sensations, you’ll be able to figure out what categories of flavors the dish’s components fall into: acidic, aromatic, fatty, salty, sweet.

Screenshot this flavor guide or download it to print, here.

Clare Marie Schneider/NPR

One rule of thumb: ingredients that fall into the same category can be swapped out for each other more easily.

Acids are flavors that add a brightness to a dish – and they’re usually sour. They include lemon or lime juice, vinegars or wines. Sour dairies like buttermilk, sour cream and yogurt are also acids.

Aromatics really affect the way your dish smells, so think about the role of spices and herbs in your dish. They include garlic, onions, ginger, cumin, paprika, parsley, basil or cilantro.

Fats are great to soften vegetables over high heat, and they can give a richness to a dish. Butters, oils, margarine, ghee all count as fats. So do cheeses, milks and creams and their vegan alternatives, and they’re usually used more to finish off a dish to make it creamy.

Salt comes in many forms: sea salt, kosher salt, table salt, coarse or fine. You can also add salt with soy sauce, fish sauce, capers, canned anchovies or bacon bits. It’s really important to taste as you salt so you don’t accidentally add too much.

Sweet ingredients include sugars, maple syrup, honey or molasses.

Taste as you go – and adjust your seasonings accordingly

One relatively fool-proof way to get your seasoning just right – whether it’s the one in your recipe or something you’re subbing in: keep tasting your dish as you go.

“You could be cooking for 20 years and still have your seasoning off in the dish,” says Deb Perelman, cookbook author and the voice behind Smitten Kitchen, one of my most trusted sources for recipes. “Taste as you go, and [your dish] won’t end up over seasoned or over-salted or under-salted.”

How much you use depends on what your substitute ingredient is. Say you want to swap in dried herbs for fresh ones, like rosemary, basil, ginger or garlic. They’re great alternatives to their fresh counterparts, but they’re also stronger in flavor, so you’ll want to use less than what the recipe calls for.

When in doubt, start with less seasoning and add more once your dish is almost done cooking. “With most flavors, it’s very easy to add things but difficult to take them away,” says López-Alt. “So as you’re tasting, you want your dishes to generally be a little bit under-seasoned through the cooking process so that you can adjust the seasoning at the end.”

How you cook your food is just as important as what you put in it

Flavor isn’t just about the ingredients in a dish, but also about the technique used to prepare it.

“If you start really sort of thinking about it that way, then you realize that cooking is not just a series of recipes, but it’s a series of techniques that you can adapt to your own taste,” says López-Alt. His latest cookbook, The Wok: Recipes and Techniques, really breaks it down.

Sometimes, searing or browning before you start adding other ingredients can add a more robust flavor to a dish. If you simmer a bunch of ingredients over the course of an hour, flavors will mingle together more intimately and develop differently than if you let them simmer together for 15 minutes. Slowly sauteing vegetables, like onions, can help them “caramelize,” or become sweet and jam-like. But if you quickly pan fry them, or roast them in the oven on high heat, they can become crispy.

Understanding the technique can give you a lot of flexibility to figure out what you can substitute – including what type of pan you should use, especially if you don’t have the same equipment a recipe suggests.

“If it’s a recipe that requires a lot of heavy searing … You generally want something really heavy that’s going to retain heat,” explains Lopez-Alt. “So you could do it in a Dutch oven, you could do it in a cast iron pan, you could do it in a tri-ply stainless steel skillet.”

If you’re stir-frying and need to change temperatures quickly, Lopez-Alt suggests a carbon steel or aluminum pan.

Remember that recipes – and recipe writers – “are not God”

A recipe is there as a guide, but it’s not the law. “We just write this stuff down because we want it to be the best-case scenario for you,” says Perlman. “We are not God. We are not here to tell you how to cook and how not to cook.”

So if you find yourself reading a recipe that asks for an ingredient that’s hard to find or too expensive, Perelman says you can ask yourself, “Is this ingredient essential? Is it a deal-breaker if I don’t have it? What’s lost if I don’t use it?”

Ultimately, “you should make food the way you want it,” says Perelman. If an experiment doesn’t go quite as planned, that’s OK.

“I think it really, honestly, all starts with just being kind to yourself,” says López-Alt, “and understanding that if you mess something up, it’s not really that big a deal.”

The podcast portion of this story was produced by Andee Tagle.

We’d love to hear from you. If you have a good life hack, leave us a voicemail at 202-216-9823 or email us at [email protected]. Your tip could appear in an upcoming episode.

If you love Life Kit and want more, subscribe to our newsletter.